The Windmill of Galati, Our Daily Bread

The Windmill House of Galati

"While the Ghinea family is a work of fiction, it is comprised from the threads of countless true Romanian lives — of homes and livelihoods built with love and lost to history, and of the quiet strength that endures long after walls have fallen."

The House on the Hill

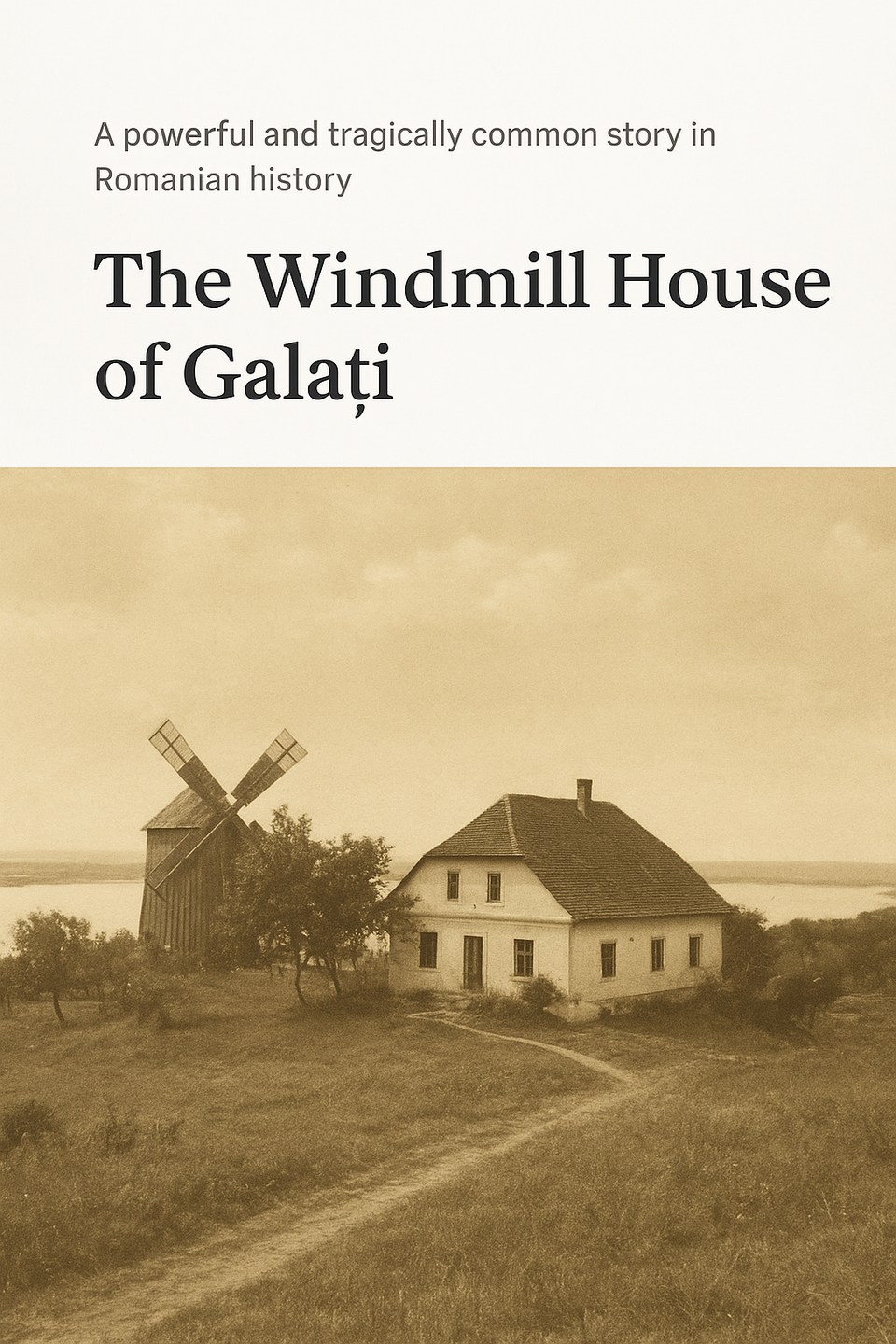

High above the curve of the Danube, before Galati’s skyline began to be populated with concrete apartment blocks, there once stood a house known simply as Moara de Vant — The Windmill.

It wasn’t grand in the aristocratic sense. Its appeal lay in its honesty — thick walls of river stone, a veranda lined with grapevines, and the steady hum of the windmill that gave it its name. Behind it, fields of golden wheat stretched toward the horizon. From the terrace, you could watch barges moving slowly along the Danube like time itself drifting eastward.

This was the home of Dimitrie Ghinea, a man who believed that work, not birthright, defined a person’s worth. Starting with a small bakery near the old market square, he built a name that became a local landmark: Ghinea Pacificate — a bakery known for its warm bread and for Dimitrie’s insistence that every customer leave with good vibes and a story.

By the late 1930s, his mill supplied flour not only to Galati but to neighbouring towns as far as Tecuci and Braila. The Windmill House was not a symbol of luxury, but of earned peace — a place where Dimitrie’s wife, Elena, tended roses, and where their two children chased each other among the apple trees.

The Night the Wind Stopped

Then came 1948.

It began with hushed rumours — new words in the air: nationalizare, chiaburi, the people’s justice. At first, Mr Ghinea didn’t believe they would come for him. He wasn’t a baron or a profiteer, neither politically motivated nor intellectual. He paid his workers fairly, gave bread to the poor. Surely that counted for something.

One night in spring, the sound of boots broke the silence. The door splintered before he could reach it. Men in grey coats entered with folded papers and cold eyes.

By order of the People’s Council, they said. The property known as Moara de Vant and all associated assets are now the property of the State.

They gave the family until dawn to leave.

Dimitrie’s hands shook as he packed. Not from fear, but from disbelief — how do you fold a lifetime into one suitcase? Elena gathered photographs, her mother’s icon, and a single loaf of bread still warm from the kitchen. Their children, silent, clung to the bannister as strangers carried furniture out into the night.

The windmill creaked as the dawn light rose. Then it stopped.

Exile in Their Own City

The Ghinea family were sent to a cramped communal apartment near the train station, sharing a kitchen with four other families. Dimitrie was labelled a bourgeois exploiter and arrested weeks later for economic sabotage. He was sent to the Canal, the brutal construction site meant to carve a shortcut between the Danube and the Black Sea — and a grave for those the regime wanted forgotten.

Elena swept streets by day and wrote to him by night. Most letters were never delivered.

Years passed. The bakery became State Bakery No. 4, its bread grey and tasteless. The Windmill House was given to a Party official, who painted it red and filled the garden with cars and loud parties.

When Dimitrie came back — thinner, older, but unbroken — he found the city had changed. Galati had grown taller, but not richer in soul. He died soon after, quietly, on a winter night, his last words a whisper to Elena: Don’t let them forget the Windmill.

What Remains

Decades later, after the Revolution, their granddaughter — Oana Ghinea, born in exile in Calarasi— returned to Galati, not for revenge, but for understanding, for closure.

The Windmill House was still there, though the windmill itself was long gone, replaced by a rusty satellite dish. The paint peeled, the garden overgrown. But when Ana pushed open the gate, the scent of apples lingered.

She walked through the empty rooms, her footsteps echoing against the silence. In the corner of the old kitchen, she found a tile with her grandmother’s handwriting scratched faintly into the plaster: Pâinea noastră cea de toate zilele — Our daily bread.

It wasn’t about bread anymore. It was about continuity — the quiet defiance of memory.

Reflections from the Danube

Today, Galati is a city that still survives through its contradictions — steel and silence, river and wind, loss and resilience. For those who come from abroad, or those who left Romania long ago and now look back with longing, stories like the Popescus’ are more than history. They are a mirror.

Every old Romanian home has ghosts — not of terror, but of endurance. Behind peeling paint and creaking gates are the dreams of people who built, lost, and still hoped. To walk through these streets is to feel that mixture of sadness and beauty that defines Romania: a country that has fallen many times, but never fully broken.

The Windmill House no longer stands as it once did, but in the scent of fresh bread from a corner bakery, in the laughter of children by the Danube, its spirit — and Dimitrie’s stubborn faith in honest work — endures.

And perhaps that is the true inheritance of this land: that the wind never truly stops — it just waits for someone new to turn the sails again.

A Reflection

At White Mountain, we often say that a home is more than a roof — it’s a vessel of memory.

Every house in Romania has a story, and some are written in history’s wind — stories of courage, loss, and return. Whether you’ve just arrived or you’re coming back after years abroad, you’ll find that what makes this country special isn’t just its buildings, but the resilience of the people who once called them home.

Every home tells a story. Some just whisper a little louder when the wind blows from the Danube.

Member discussion